![Lapis armenus]()

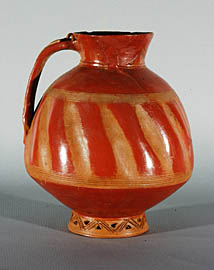

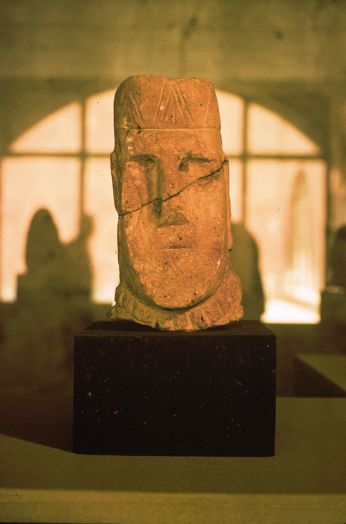

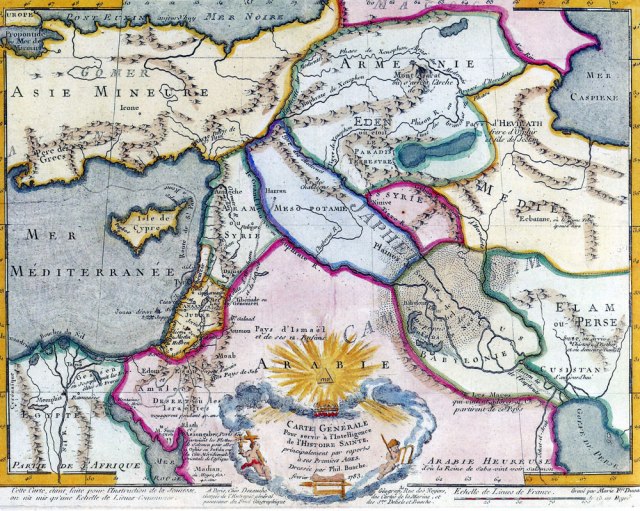

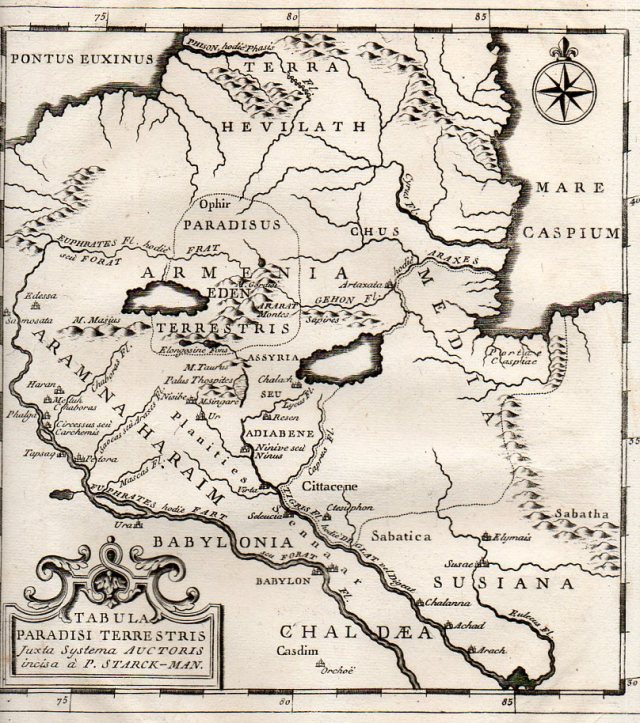

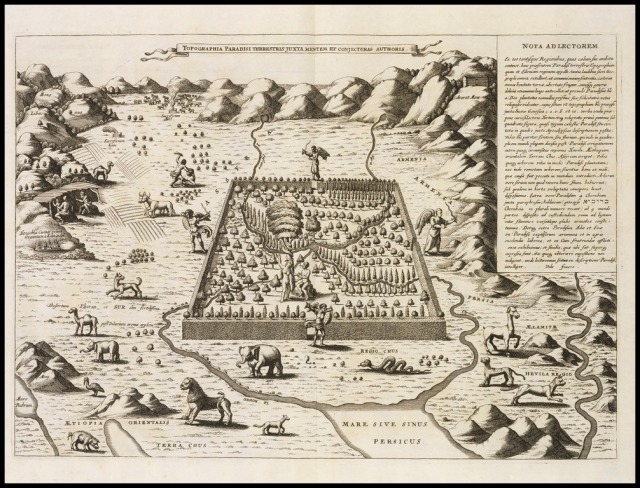

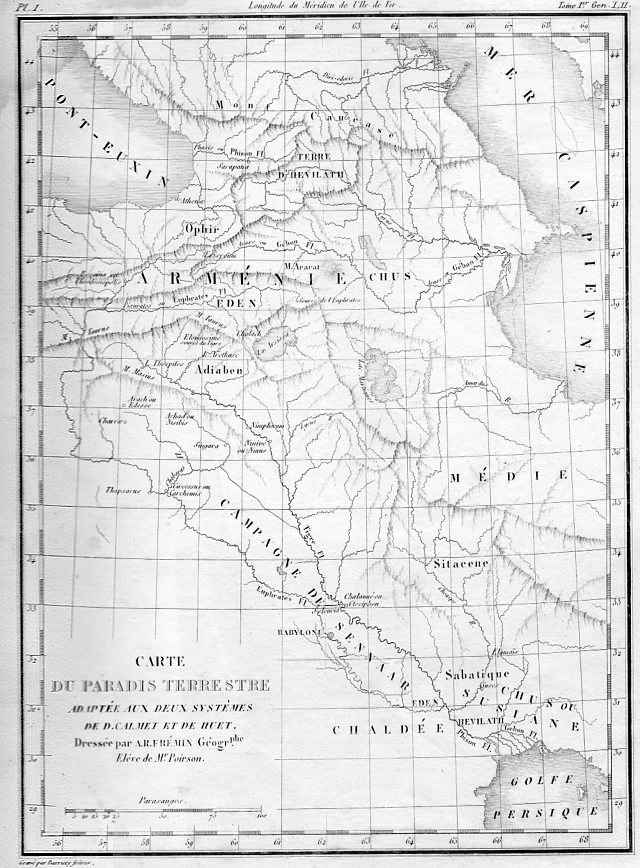

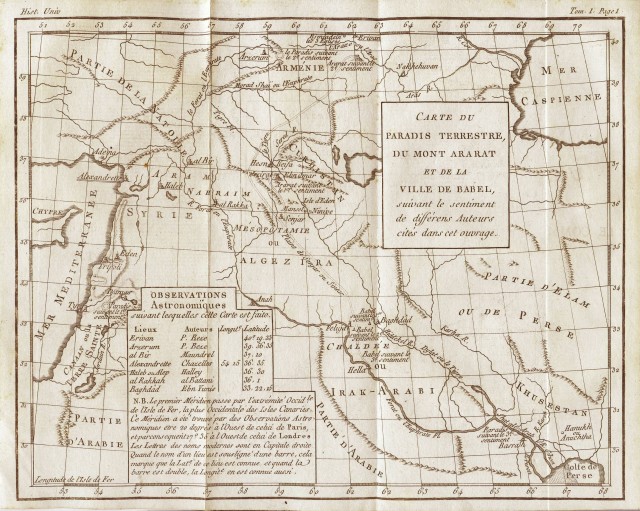

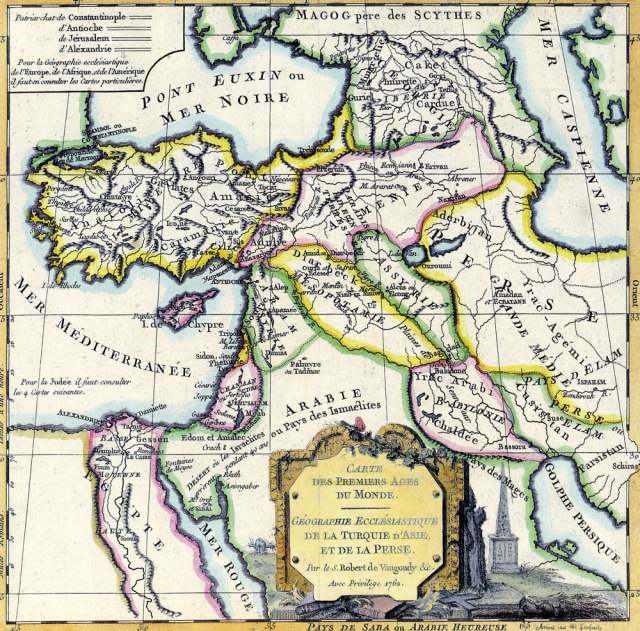

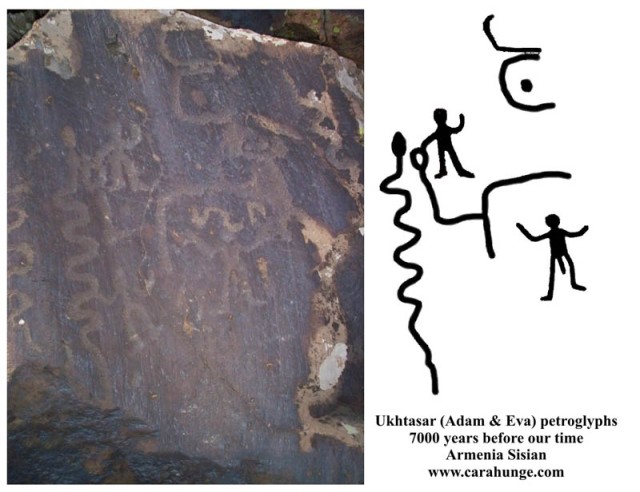

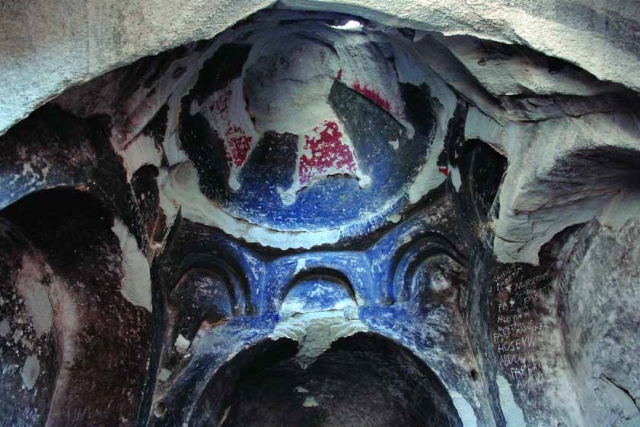

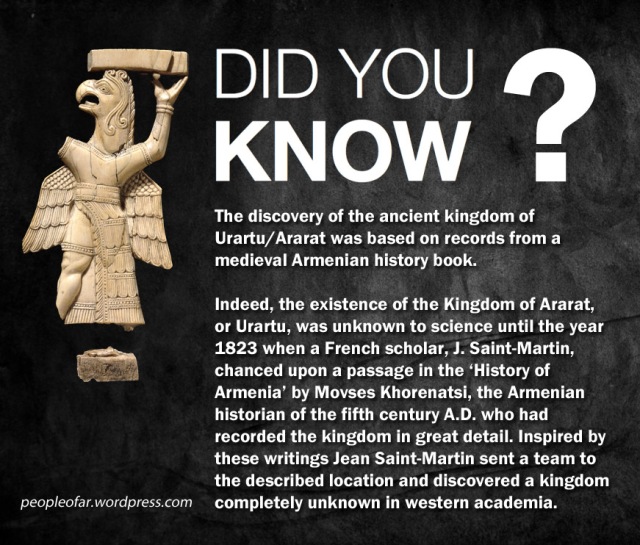

Aratta is a mountainous land that appears in Sumerian myths identified by various scholars with Ararat (Ayrarat) of historical Armenia.[1][2][3][4][5] Aratta was considered a holy site (home to the goddess Inanna, analogue of Anahit) [6][7][8] famous for metallurgy, stone masonry, gold production, silver and their precious blue Azurite stones. Since the antiquity Armenia was known for the best quality of these mineral stones which are called Lapis Armenus, also known as Armenian stone in natural history. Lapis Armenus is a variety of precious blue Azurite stone, nearly identical to the Azurite known as lapis lazuli, occasionally used interchangeably [9][10] but distinguished by a finer structure sometimes containing greenish tints. The 1816 Encyclopedia Perthensis notes that Armenian stone “was anciently brought from Armenia to Europe”. Emanuel Mendes da Costa (1757) describes it having: “an elegant bright or clear blue color, sometimes of a deeper sometimes of a paler blue, and also sometimes with a greenish cast.”[11] The blue of Azurite is exceptionally deep and clear, and for that reason the mineral has tended to be associated since antiquity with the deep blue color of low-humidity desert and winter skies. Lapis Armenus was highly esteemed in antiquity, and attempts have been made to recreate it artificially. Sumerian king Enmerkar (ca. 2100 BC) in the epic “Enmerkar and the lord of Aratta” prays to the deity Inanna asking her to bring him precious materials from Aratta, including Azurite blue stones called “za-gin” in Sumerian epics.[12]

“My sister, let Aratta fashion gold and silver skilfully on my behalf for Unug. Let them cut the flawless [za-gin] (Azurite) from the blocks”… “Let the people of Aratta bring down for me the mountain stones from their mountain, build the great shrine for me, erect the great abode for me…”

John Hill (1748) in his work on minerals gives a historic account of the Armenian stone, describing it as follows:

“A glorious color for painting, and was in the highest esteem as such among the ancients. Theophrastus has recorded it, p. 130. that it was a thing judged worthy of a place in the Egyptian annals, which of their kings had the honor of inventing the factitious kind : and that it was a substance of that value, that presents were made to great persons of it ; and that the Phoenicians paid their tribute in it.”[13]

To some Greek writers it was also known as ‘kuanos’ (κυανός: “deep blue,” root of English cyan) and in Latin ‘caeruleum nativum’ (native blue or sky blue) usually mixed with green elements (called Chrysocolla).[13] Theophrastus (c. 315 BC) confirms that “the native kuanos” (or Lapis Armenus) has in it “Chrysocolla,” which, to the ancients, was a green oxide of copper.[14] Referring to the Armenian stone Pliny the Elder (1st c. AD) in his Natural History describes its preparation as follows:

“When chrysocolla has been thus dyed, painters call it “orobitis,” and distinguish two kinds of it, the cleansed orobitis, which is kept for making lomentum, and the liquid, the balls being dissolved for use by evaporation. Both these kinds are prepared in Cyprus, but the most esteemed is that made in Armenia, the next best being that of Macedonia: it is Spain, however, that produces the most. The great point of its excellence consists in its producing exactly the tint of corn when in a state of the freshest verdure. Before now, we have seen, at the spectacles exhibited by the Emperor Nero, the arena of the Circus entirely sanded with chrysocolla, when the prince himself, clad in a dress of the same colour, was about to exhibit as a charioteer.”[15]

The classical author Vitruvius (1st century BC) lists the Armenian stone by the name of Armenium and Pliny (77AD) lists this among his ‘florid’ colours (at a massive 300 sesterces per pound).[16] In the 1759 book “The Modern Part of an Universal History” the authors mention Lapis Armenus whose veins “naturally represent flowers, trees, mountains and rivers.” And from it tables and other ornaments are being made.[17] Theophilus (1847) in his work also mentions its ornamental usage:

“The deep blue, “Lapis Armenus” or cyanus, is even now cut for ornaments ; some of this so closely resembles sapphirus or lapis lazuli that it is only by the test of fire, which destroys the blue colour of the native carbonate of copper, the two are to be distinguished.”[14]

The Azurite Lapis Armenus is often found in association with another copper carbonate; the Malachite [18] also known as the green lapis lazuli (also identified with the Latin Chrysocolla).[19] The Sumerian epic “Lugalbanda and the Anzud bird” mentions this Malachite in Arrata:

“Aratta’s battlements are of green lapis lazuli, its walls and its towering brickwork are bright red, their brick clay is made of tinstone dug out in the mountains where the cypress grows.” [20]

Classical historians would still remember these ancient mines. Roman physician Pedanius Dioscorides (1st century AD) says that the “finest comes from Armenia, the next best from Macedonia and after that the Cyprus, but this mineral is not obtained from any of these places today.”[21] It is also known to have been used for coloring ancient Chinese porcelain.[22] The Armenian Azurite has been used as a pigment as early as the Fourth Dynasty in Egypt. It was no doubt the most important blue pigment in European painting from the fifteenth to the middle of the seventeenth century. The paintings of that period contain more ultramarine made from lapis Armenus, than from any other substance.[29]

From Armenia to Babylon

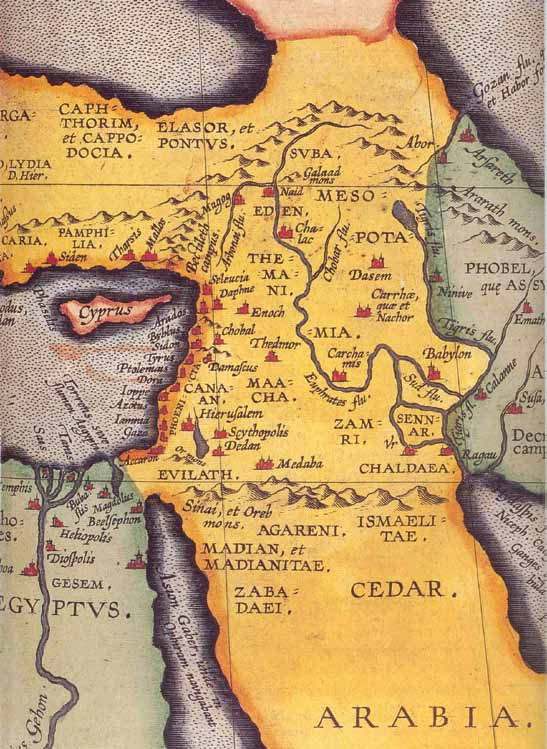

![Babylonian map of the world (6th c. BC)]()

Babylonian map of the world (6th c. BC)

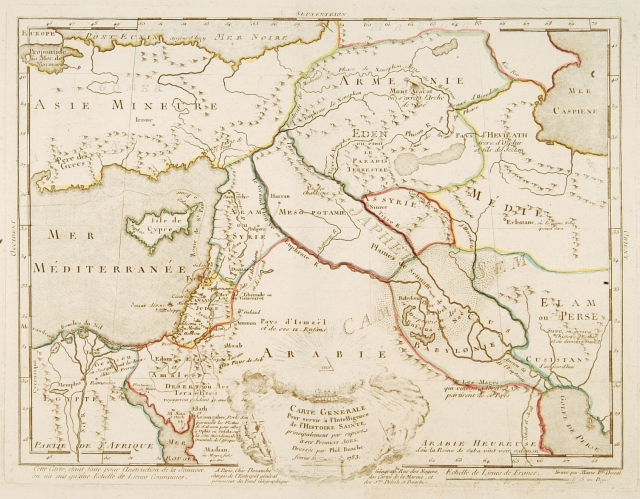

The method of transporting the “stones of the mountain” from Aratta to Uruk and of transporting grain from Uruk to Aratta, as described in the Sumerian myths, seems consistent with such trade historically between the Armenian highlands and areas to its south, namely, by boat from Aratta toward the south, and by pack animal from Uruk towards the north. Extensive trade between Armenia and Babylon was well known in the ancient world. The Greek historian Herodotus (c.a. 450 BC) in his work “The Histories”: I:194 provides some details on cargo transport between Armenia and Babylon:

But the greatest marvel of all the things in the land after the city itself, to my mind is this which I am about to tell: Their boats, those I mean which go down the river to Babylon, are round and all of leather: for they make ribs for them of willow which they cut in the land of the Armenians who dwell above the Assyrians, and round these they stretch hides which serve as a covering outside by way of hull, not making broad the stern nor gathering in the prow to a point, but making the boats round like a shield: and after that they stow the whole boat with straw and suffer it to be carried down the stream full of cargo; and for the most part these boats bring down casks of palm-wood filled with wine. The boat is kept straight by two steering-oars and two men standing upright, and the man inside pulls his oar while the man outside pushes. These vessels are made both of very large size and also smaller, the largest of them having a burden of as much as five thousand talents’ weight; and in each one there is a live ass, and in those of larger size several. So when they have arrived at Babylon in their voyage and have disposed of their cargo, they sell by auction the ribs of the boat and all the straw, but they pack the hides upon their asses and drive them off to Armenia: for up the stream of the river it is not possible by any means to sail, owing to the swiftness of the current; and for this reason they make their boats not of timber but of hides. Then when they have come back to the land of the Armenians, driving their asses with them, they make other boats in the same manner. [23]

Medicinal Powers of Lapis Armenus

![Lapis Armenus medical value]()

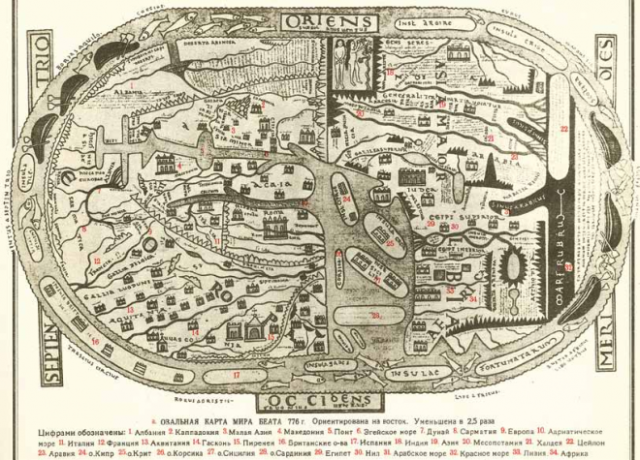

From “The Anatomy of Melancholy, what it is: With All the Kinds, Causes, Symptons, Prognostics, and Several Cures of it, Volume 2″ by Robert Burton (1871)

Lapis Armenus has often been credited with medicinal and sometimes even magical powers. Among many other things lapis Armenus was used to cure depression, elephantiasis, asthma, kidney problems, infections and melancholia. [24] In medicine according to Dr. Grew (1757), “it is highly celebrated by some, not only for its innocent and most easy, but also most effectual operation, in such diseases as are supposed to depend on melancholy.”[11]. Nicholas Meripsa puts it among the best remedies, in his book Antidotis: “and if this will not serve (saith Rhasis) then there remains nothing but Lapis Armenius and hellebore itself.”[25] Similarly, Isidore Kozminsky (2012) in his recent book “Crystals, Jewels, Stones: Magic & Science” describes some of its medical properties:

“Lapis Armenus, or Armenian Stone, is a copper carbonate used as a medicine against infection. It is related in Arab books that a solution of this substance will retain its power for 10 years. In the East copper has been long used as a safeguard against cholera, and it has been observed that workers in copper mines have enjoyed immunity from the disease. The Lapis Armenus, like all copper compositions, is under the rule of the planet Venus.” [26]

Burton (1871) recounts physicians who speak highly of this substance:

“”That good Alexander” (saith Guianerus) “puts such confidence in this one medicine, that he thought all melancholy passions might be cured by it; and I for my part have oftentimes happily used it, and was never deceived in the operation of it.” The like may be said of lapis lazuli, though it be somewhat weaker than the other. Garcias ab Horto, hist. lib. 1. cap. 65.relates, that the physicians of the Moors familiarly prescribe it to all melancholy passions, and Matthiolus ep. lib. 3. brags of that happy success which he still had in the administration of it.”[25]

In the Arab world Lapis Armenus was famously used by doctors as a remedy or natural cure against vertigo, melancholia, and epilepsy. The lapis Armenus was well known to the Arabs under the name “Hajer Armeny”, and their medical writers describe it quite accurately. Ibn Beithar states that if properly prepared it would not provoke nausea, as was otherwise the case. It was said to cause a very abundant evacuation of bile and must have been regarded as an efficient remedy for the bilious disorders so general in warm climates.

A “blue amulet” against vertigo, melancholia and epilepsy could be made up of the following ingredients: shavings from an elk’s horn and from a human skull, to be reduced to a fine powder, the excrement of a peacock, white agate, lapis lazuli or lapis Armenus, of which enough was to be used to give the required sky-blue tint. The whole mass was then to be softened by the addition of gum tragacanth, and formed into heart-shaped tablets, which were to be dried out in the air, and then smoothed on a turning-lathe. These amulets were to be worn attached to the neck or the arm, sometimes they were enclosed in a little receptacle of silver or of red sandal-wood and suspended from the neck. (J.J. Kent, 2004)

Regarding the length of time during which various preparations retained their strength, Braunfels (1997) states that, according to the opinion of the Arabian physicians, the solution of lapis Armenus lasted for ten years, while that of lapis lazuli could be preserved only about three years. [28] Pliny too mentions a blue Azurite pigment from Armenia, which was used “in medicine to give nourishment to the hair, and specially the eyelashes” (N.H. 35:28) [19] Physicians used to select lapis Armenus that is smooth, blue, non-granular and easily pulverized. [21]

SOURCES:

[1] Kavoukjian M. (1978) Armenia, Subartu and Sumer

[2] Nazaryan G. (2008) Armenian Highland

[3] Movsisyan A. Armenia in spiritual concepts of Ancient world. Armenological Encyclopedia

[4] Artak Movsisyan (1992) Aratta: The ancient Kindgom of Armenia, Yerevan

[5] Artak Movsisyan (2001) Aratta: Land of the Sacred Law, Yerevan

[6] Boyce, Mary (1982), A History of Zoroastrianism, Vol. II, Leiden/Köln: Brill

[7] Cumont, Franz (1926), “Anahita”, in Hastings, James, Encyclopedia of Religion and Ethics 1, Edinburgh: T. & T. Clark

[8] Lommel, Herman (1927), Die Yašts des Awesta, Göttingen-Leipzig: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht/JC Hinrichs

[9] George Perkins Merrill, Margaret W. Moodey, Edgar Theodore Wherry (1922) Handbook and Descriptive Catalogue of the Collections of Gems and Precious Stones in the United States National Museum, Issues 118-120

[10] 1998 Webster’s

[11] Emanuel Mendes da Costa, (1757). A natural history of fossils

[12] Enmerkar and the lord of Aratta, ETCSLtranslation : t.1.8.2.3

[13] John Hill, Thomas Osborne, (1748) A General Natural History Or, New and Accurate Descriptions of the Animals, Vegetables, and Minerals, of the Different Parts of the World

[14] Theophilus (1847), Theophili, qui et Rugerus, presbyteri et monachi, libri III. de diversis artibus: seu, Diversarum artium schedula

[15] Pliny the Elder, ( 1st c. AD ) The Natural History, Chap: 27

[16] Valentine Walsh, Tracey Chaplin (2008), Pigment Compendium: A Dictionary and Optical Microscopy of Historical Pigments, Routledge

[17] S. Richardson, T. Osborne, C. Hitch, A. Millar, John Rivington, S. Crowder, P. Davey and B. Law, T. Longman, and C. Ware, (1759) The Modern Part of an Universal History: From the Earliest Account of Time. Compiled from Original Writers. By the Authors of The Antient Part

[18] Dictionary of Traded Goods and Commodities, (1550-1820) British History Online

[19] George Robert Rapp (2009) Archaeomineralogy

[20] Enmerkar and the lord of Aratta, ETCSLtranslation : t.1.8.2.2

[21] Geological Society of America (1955), De Natura Fossilium: Textbook of Mineralogy

[22] Charles Alfred Speed Williams (1941), Chinese Symbolism and Art Motifs: An Alphabetical Compendium of Antique Legends and Beliefs, as Reflected in the Manners and Customs of the Chinese

[23] Herodotus (c.a. 450 BC) The Histories: I:194

[24] C.J. Duffin, R.T.J. Moody, C. Gardner-Thorpe, (2013) A History of Geology and Medicine

[25] Robert Burton (1871), The Anatomy of Melancholy, what it is: With All the Kinds, Causes, Symptons, Prognostics, and Several Cures of it, Volume 2

[26] Isidore Kozminsky, (2012), Crystals, Jewels, Stones: Magic & Science

[27] J.J. Kent, 2004

[28] George Frederick Kunz, (1997) The Magic of Jewels and Charms

[29] Attila Gazo (2010) Attila Gazo

![]()

![]()